- Home

- Francesco Pacifico

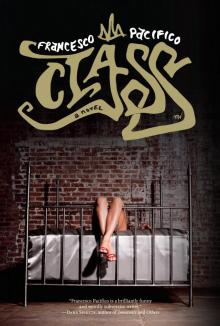

Class Page 2

Class Read online

Page 2

You come from a good family: your parents used to vote for the Communist Party; they taught you to make time for the soup kitchen on Sunday mornings, to spend late winter afternoons at nursing homes, at senior citizens’ dancing groups. But your progressivism was unanchored from theory, estranged from the Marxism you never even knew you had outgrown. What was once open-mindedness became pure exoticism: culture was for collecting. You’re only good for hailing cabs and booking flights that expand your carbon footprint. You refresh ryanair.com while—far from your eyes and farther from your heart—exhausted old ladies crouch on their knees in an industrial Chinese suburb, pulling obsolete cell phones from heaps of waste, from the sewage of techno-capitalism. You watched the Edward Burtynsky documentary that night at the Kino club, the one with the uranium mines and the nickel residue piercing the dark Ontario earth like lava, and those old Chinese ladies, hunched over piles of electric circuits…

January 10, a Monday. The sidewalks are covered with snow. The whole city is a uniform shade of blue; there’s no air, only color. La Sposina walks out of the secondhand boutique where she works part-time, her laptop in a huge, stylish bag lent to her by her boss, and no fresh underwear. She has just made up her mind: she’s going to spend the night out without informing Lorenzo. She walks down Bedford toward the subway station, shivering with cold, alert to ice, her Uggs ready to betray her at any moment.

Yesterday she spoke her mind for the very first time: “I need to go back to Rome and deal with the bookstore. And you’re, what, you’re going to stick around for this…film thing? You’re thirty-four. Is any of this going anywhere? Are you?”

Her husband made sure to not quite understand. In the moment, he believed his own incomprehension: “I don’t get how your father can tell you that you should feel free to go to New York, no problem, and then tell you to come back as soon as he needs you. You’re married to me, not him.” He was standing on the uneven floor, his eyelids and lashes doing the work of a smile. Ludovica gazed at him from the couch. She was sleepy and unmoored, and she found him attractive.

The Portuguese boyfriend of one of the flatmates—the one from Turin—had come by the shop a few days earlier and hung out for an hour while Ludovica showed him Lorenzo’s short film on the shop’s computer, on YouTube. He hadn’t understood that this was Lorenzo’s movie, didn’t recognize La Sposina in the two scenes she appeared in. “Oh my god this is so bad,” he groaned, laughing meanly but honestly. Ludovica chalked it up to jealousy (would he and the flatmate ever start shooting that documentary about the Macy’s on Fulton Street? Of course not), but still, the idea that the movie didn’t meet with international critical approval led her to watch it over and over again the following weekend. It seemed well directed and clever, so…what was the problem?

Maybe she was jealous of Lorenzo, too. He was out with the Italian movie buffs every night—the haters called them the cinematografari romani—spending far too much money at the IFC, at Angelika, at Film Forum. Even in the winter, when his clothes were buried under his horn-buttoned Montgomery coat, he had the air of somebody who’d make the most of his appearance to win the hearts of the daughters of Roman politicians and Milanese publishers—that wealthy, rascally aura. He made his way among them like he knew he was a good fuck, a master of the signals. He left her at home, in bed, on Friday night and Saturday night and Sunday night. She begged him to stay; she was weary from the winter snow, she wanted to make love and laze around in bed. He made fun of her when she told him (gracefully, gently, with an eyebrow lifted the right way, ever willing to blow him) that maybe he shouldn’t come on to these women so much, make himself seem less available. In reply he gave her his Latin smile, his unbuttoned white shirt smile, his unlaced Campers smile. He enjoyed the display of jealousy, and he wouldn’t change a thing.

But if it turned out that Lorenzo had no talent, the behavior she’d always condoned could no longer be written off as light and careless. It was vain, and she didn’t think she deserved a vain, talentless husband. But was he talentless or not? She was consumed with doubt! Which was why she told him to ask himself a question: should he keep calling himself a filmmaker forever if he was really just a philosophy student, a perpetual apprentice in the philosophy of science? But he wouldn’t listen. So she’d be spending the night out of the apartment.

Fifty yards from the train station, she’s breathless. She fears she might stumble and hurt herself. A few months ago, a doctor found a blood clot in the back of her neck, so every day at five, she swallows blood thinners to avoid an embolism in the right lateral sinus. If she so much as nicks her leg while shaving, it can take an hour to stop the bleeding. She changes her mind and hails a cab, gets into a yellow SUV that stops at the corner of Bedford and Metropolitan.

—

MAYBE SHE’LL CRASH with Berengo. She hasn’t called him, hasn’t even run into him since last fall.

The driver is a big African guy in his early forties, Ghanaian. He’s Catholic and has many questions for her—all about Rome—which he asks as they drive up the ramp to the Williamsburg Bridge. There’s a picture scotch-taped to the dashboard, his three children in their Sunday best: two girls in emerald dresses, a boy in a turquoise suit.

After dark, the bridge is a necklace of white lights, but now, when the sun is weak and the shadows are faint, it’s gray and blue and maybe pink, comforting and fatherly. What she’d really like to do is put her earphones in and listen to “Empire State of Mind” and weep as the skyscrapers rush toward her. She sees many New Yorks at once. The cab driver is eighties Jarmusch, independent film, the world as it was before the Lorenzos of the world found out enough about it to co-opt it. The bridge is something more Hollywood—Woody Allen, maybe, or Sex and the City—the New York all Italians celebrate and suck up to. She compromises: the right earphone for “Empire State of Mind,” the left ear for the driver. She asks him questions, tracks his answers. He did well in Atlantic City, where he was a croupier in a Trump casino. (Queste strade ti faranno sentire nuova, le luci forti ti ispireranno.)

“Where did you learn?”

“Atlantic City croupier school.”

“Was it expensive?”

“Very.”

“How much?”

“Fifteen hundred dollars.”

She feels relieved because that doesn’t sound like much.

“So why did you stop?”

“I got asthma. Too much secondhand smoke.”

Halfway across the bridge, she puts in the second earphone, the song on repeat, le luci forti ti ispireranno, to let the feeling live on. The driver brakes and throttles in sharp bursts, every shift in speed a punch in the stomach. The hot air is on full blast, and it makes the artificial leather feel sticky. Still, she knows that this—the sun, the iron, the skyline, the song—will mold itself into a happy memory. She’ll tell her mother and her friends about it, she’ll tell Lorenzo. She can imagine the conversations now, they’re happening in her mind. By the time she says any of it out loud, she’ll have edited this afternoon drive into a perfect scene, free of unhelpful context…

The island is rushing toward you. It’s dense with blood and drive and contains within it most of the earth’s ambition. There are more exciting megalopolises out there—cities like Shanghai and Abu Dhabi, grander versions of Manhattan, the original re-created in the middle of deltas and deserts—but as new rivals emerge, the scale of New York’s ambition, its hunger, never dips. From the queers in the Theater District to the Canal Street vendors who shove fishnet stockings into tourists’ arms to the jewelry store owners huddled in Midtown, everyone has a raging boner they’re so desperate to release that it’s like the whole city is an eight-year-old boy writhing in his bed with his first erection (this is Lorenzo’s imagery); entering the city via the bridge, in a cab, you’re a fresh drop of blood in the world’s grand cock (still Lorenzo’s imagery). And blood is what the world longs for on, say, a sunny Monday morning, when women who dried their hair too quickly

step out of dark lobbies and get hit with wind and headaches, when firemen on gleaming trucks hurry to save office workers trapped in skyscrapers and preserve man-hours, because someone left a scented candle lit last night, working overtime, when the dirty snow near the curb looks to bigger, fresher flakes for cover (another storm is due tomorrow), when the gray pigeons—true city dwellers—fly from one eave to another in twenty-unit gangs, and every neighborhood begins to speak its own language again: the laundromats, the liposuction ads, the satisfied chatter of a businessman from Alabama in town for the week, the girls with their long straight hair, their bangs…

On the bridge, caught in the middle of flowing traffic, she can see the city parting its hair on either side of Delancey. The grim, blocky high-rises along Houston remind her of some past she doesn’t quite recall, the murals on windowless facades seem knowable. “È un giorno così crisp, mamma, you’d love it,” she says to herself in half-English, half-Italian, a made-up language that makes her feel grand.

Cabs assail the city from all sides. They attack from every bridge and tunnel, an army, an endless scroll of cabs whose drivers never seem to stop for naps or lunch or to go to the bathroom. They’re a constant, e se ce l’ho fatta qui ce la posso fare dovunque.

She blocks the storefronts with her hands and looks up at second floors to discover an essence: New York before Duane Reade. Many of the buildings are in shadow, almost black, but some are clear and bright, more pristine than a sunbeam. The city cycles between darkness and light, unsteady, like something out of a Meyerowitz photograph…

—

A NINETIES-ERA SKYSCRAPER: bland, hazel bricks, less glass than one would expect. The building looks corporate and defensive, but the Latin doorman bows as he opens the door for her, greets her with a smile. La Sposina steps onto the green carpeting, walks toward reception among mirrors and fake art deco. Now another handsome employee—say, Chazz Palminteri in Bullets over Broadway—calls up to Berengo’s apartment.

He’s not in, and his mobile isn’t working, so you leave a card for him and walk out. Berengo gave you the card at that party back in October—VALID THRU 2011, it says—as a gesture of hospitality for whenever you found yourself fed up with Lorenzo. There’s a Hello Kitty sticker on the back.

Out on the street, you’re less afraid that you’ll slip and fall in the snow, because everything in Manhattan is more thoroughly maintained. You walk down Eighth Avenue and look for a place where you can wait for Berengo to come back. You pass a couple of ugly and anxious shops so eager to please that they please no one; a one-dollar oyster place packed with bros in puffy jackets; a lurid Italian place on a dead corner, almost hidden under scaffolding. Finally, you find it: the Cosmic Diner, perennial, greasy, half-filled with ugly people sectioned off in green booths. A big, bald Jewish man with a machine-refined beard, stout but crumbling. A black woman with a grim, round face. A white man in a dull, gray jacket eating tomato soup, the melted cheese clinging to his spoon as he stares at his Kindle.

Sometimes, when you squeeze your cheeks together and your cheekbones protrude, you think you look like an Italian actress, Jasmine Trinca, star of popular yet somehow engagées films like La meglio gioventù and Romanzo criminale. Trinca always plays the outraged type, keen and sharp but quick to resolve misunderstandings with her hopeful, empathetic smile. When Trinca was beginning to break out, you were often told you looked like her, so you began to affect her grimace, alternating between discouragement, moral tension, and optimism. Those sexy, streamlined cheekbones helped you cycle between the three emotions, one after the other. You sit at the counter and order coffee and make faces at the mirror. The counter guys all notice you. You take Mrs. Dalloway out of your bag.

—

LUDOVICA LIFTS HER eyes up from the scene where Peter Walsh exchanges a passionate but renunciatory glance with a woman—a stranger—as he drifts around London. She spots Berengo, who’s back from a jog in Central Park. He’s wearing high-tech black leggings, a sleek windbreaker, and fuchsia Nikes by Jun Takahashi, which she identifies—admiringly—by sight. Berengo is short and fine assed, she thinks. His nose is okay, though maybe slightly too narrow, too simple. There are dark circles under his bright green eyes. He’s friends with the waiters, and though he greets her with a big smile, he never gets too close—he keeps checking his phone to avoid shaking her hand or kissing her. He’s clean-shaven under his baseball hat, which he rests on the counter. This is the first time she’s seeing him this way: as someone connected to her and not to her husband.

How strange for me to see her in the company of my beloved Nico Berengo.

They move to a booth. The benches are uncomfortable, oddly vertical. Berengo seems so sweet to me, so easy, but to her he’s an enigma.

“How are you?” he asks. “Have you eaten?” He doesn’t listen for her answers. He keeps his iPhone in his left hand, reads the menu, makes small talk with the waiter, orders an Orange Crush, wishes he hadn’t. “So, tell me.” The phone is still in his hand.

She laughs, kind of. “I don’t know where to start.”

Nicola catches his breath, frowns. “You’ve fled home, right? You’re out to find yourself a lover.” He’s baby-faced and wrinkly.

He asks her if she minds if he answers an email or two. Between sentences, he lifts his eyes to glance at her as she eats. Ludovica pulls her phone out and slowly chews her Cobb salad.

The waiter brings Nicola an avocado cheeseburger, though Ludovica didn’t see him order. Finally, he rests his iPhone on the table and starts eating. “So, my Hello Kitty card.”

“Right.”

“My card. You’re here for that, right? So, what, you ran away from home? Do you need a new home?”

“Can’t we just talk for a minute? Just hang out?”

“You’re blushing.” He wipes his mouth with a napkin, puts it down and strokes her cheek. She withdraws at his touch.

“I didn’t leave home. I just came to ask you something.”

“So go ahead.”

“Do you…do you think Lorenzo should actually give the New York Film Academy a shot? Should he go?” If Berengo responds with a simple, straightforward “yes,” that might even be enough. She’ll walk over to Ninth Avenue, find another cab, go back to Williamsburg as if nothing ever happened.

“Oh, come on…”

“I trust your judgment. I don’t know if I trust anyone else’s.”

“You can’t ask me! It’s his decision.”

“Just tell me your personal opinion.”

“No, no, I can’t. It’s a big deal, and there’s no way I can be involved.”

La Sposina can’t seem to swallow the croutons in her salad. She takes a sip of water too quickly and stands up to cough.

Berengo wipes his hands and his mouth with the little napkin from under his glass and stands up slowly. He slides out of the booth and faces her, his mouth still full, his gaze absent and clumsy. He takes her hand and brings it to his chest.

“Are you okay?”

“Yes.”

“I’m sorry. Please, sit down.” He takes a sip of the Orange Crush through a straw. “I was just surprised to hear from you. I get…emotional when a woman enters my life like this. I start wondering if I’m ready to give her everything she needs. Take your time, tell me everything.”

Her throat swells.

“You’re right, I should have called you first…I don’t know. I’m mad at Lorenzo.”

“Is he flirting too much?”

“Why would you say that?”

“I don’t know…From Facebook? I see pictures, and he always looks like he’s…posing.”

This makes her smile.

“Do you want revenge? Want me to buy you a drink and smoke you up and get you to climax?”

She knows that this is how Lorenzo talks to women, so she changes the subject and mentions her blood clot; her mother’s constant fear that she’ll die suddenly, unpredictably; the way she didn’t want her to leave Rome. “B

asically, deoxygenated blood flows down through these two arteries once it’s supplied the brain,” she says, touching the sides of her neck with her hands. This seems to calm him down. “If you have a blood clot, it’ll swell, and you’ll have a headache that won’t ever seem to stop. One time, I noticed something was wrong just because I scratched my eye and had this crazy reaction: the sclera swelled so much, it was pink…”

“What’s the sclera?”

“The white in your eye. It swallowed my pupil.”

He listens, impassive.

“I was seeing all these little snakes swimming around in my eyes. I stayed home with the curtains down, just stuck in bed. I couldn’t move, or I guess I could move, but I didn’t want to try. Whenever I did, the blood would start circulating too quickly and fill my veins.”

Even as he returns to his iPhone activities, Nicola lifts his eyes and nods. “Poverina,” he says gently.

“With the thinners, I can get a bruise just from you touching me. And then it lasts a month.”

“That sounds sexy. Does Lorenzo like it?”

“A little bit. But I need to take some time off.”

“Too violent?”

“You mean the bruises?” She laughs. “No.”

“Go ahead, smile.”

—

THE DOORMAN GREETS her but not Berengo. On the eighth floor, they emerge onto a beige landing, dull and anonymous. A dog is barking somewhere down the hall.

In the apartment, Nico points toward an L-shaped couch under the L-shaped window. The window takes up most of the south-facing wall and stretches north for a few feet along the building’s western side. New Jersey—an inscrutable hill, vague and ominous—looms across the river. Manhattan appears in fragments: slivers of Midtown skyscrapers, the snowy rooftops of nearby brownstones, the vivid, atavistic green of the McGraw-Hill Building next door to the half-dead Port Authority.

Berengo kneels down in front of the couch to pull out the extension, puffing with effort. Physical task accomplished, he pulls some sheets and a towel from the hall closet and drags a bamboo screen in from the bedroom to give La Sposina some privacy. He doesn’t smile and doesn’t say anything, yet he doesn’t seem displeased, either—merely vacant. He shuts himself in the bathroom, and she lies down on the couch, letting her calves unwind.

Class

Class